Introduction

In the evolving landscape of systems integration, performance is not just about raw speed—it’s about scalability, efficiency, and the trade-offs inherent in design choices. This issue explores how theoretical frameworks like Amdahl’s Law and Big O notation illuminate the practical differences between Bash scripting and C++ implementations in real-world workflows.

Amdahl’s Law and Parallel Limits

Amdahl’s Law reminds us that the maximum speedup achievable by parallelization is constrained by the fraction of the workload that must remain serial. Formally:

Where P is the parallelizable portion and N the number of processors.

- Bash scripts often rely on sequential execution, with limited parallel constructs (e.g., xargs -P, GNU Parallel). Their performance gains plateau quickly because much of the orchestration remains serial.

- C++ code, by contrast, can leverage fine-grained multithreading, lock-free data structures, and optimized libraries. This allows higher values of P, pushing scalability closer to theoretical limits.

Big O Notation and Algorithmic Complexity

Big O notation provides a lens to evaluate algorithmic efficiency independent of hardware.

- Bash excels at quick orchestration of system utilities but often incurs overhead from process spawning and I/O redirection. A simple loop over files may operate in O(n), but with significant constant factors due to shell overhead.

- C++ implementations can reduce overhead by operating directly on memory structures, yielding tighter control over complexity. For example, a hash map lookup in C++ runs in expected O(1), while the equivalent Bash solution might involve repeated grep calls, effectively O(n).

C++ vs. Bash: Practical Trade-offs

- Bash Strengths: Rapid prototyping, portability, and leveraging existing system tools. Ideal for small-scale automation.

- C++ Strengths: Performance-critical workloads, scalability, and integration with complex data structures. Essential when algorithmic efficiency and parallelism matter.

- Interop Insight: The choice is not binary. Bash can orchestrate, while C++ can execute the heavy lifting. Together, they embody the principle of hybrid optimization—using the right tool for the right layer.

Bash vs. Managed vs. Native: A Performance Spectrum

🐚 Bash (Scripting Layer)

- Strengths: Rapid prototyping, portability, and orchestration of system utilities.

- Limitations: – Heavy reliance on external processes → high overhead. – Sequential execution dominates, limiting parallelism. – Complexity often grows linearly with input size (O(n)), but with large constant factors.

⚙️ Managed Languages (Java, C#)

- Strengths: – Rich runtime environments (JVM, CLR) with garbage collection, type safety, and extensive libraries. – Built-in concurrency primitives (threads, async/await).

- Limitations:- Runtime overhead (JIT compilation, garbage collection pauses).- Performance ceiling lower than native code due to abstraction layers.- Parallelism improves throughput, but serial runtime services (GC, JIT) remain bottlenecks.

🚀 Native Languages (C++)

- Strengths:- Direct compilation to machine code → minimal overhead.- Fine-grained control over memory, threading, and synchronization.- Optimized data structures (e.g., unordered_map with expected O(1) lookups).

- Limitations:- Higher development complexity.- Requires explicit management of concurrency and memory safety.

Why Native Code Outperforms

Native C++ implementations outperform Bash and managed languages because they minimize abstraction overhead and maximize hardware utilization.

- File I/O: Bash relies on shell redirection; managed languages abstract streams; C++ can use memory-mapped files for near-direct disk access.

- Parallelism: Bash offers limited parallel constructs; managed runtimes introduce scheduling overhead; C++ threads map closely to OS threads, reducing latency.

- Algorithmic Efficiency: Bash often delegates to utilities with O(n) scans; managed languages optimize but still incur runtime costs; C++ can implement lock-free structures with near-constant-time operations.

Amdahl’s Law Across the Spectrum

Amdahl’s Law explains why native code gains the most from parallelism:

- Bash: P (parallelizable fraction) is low because orchestration and I/O dominate. Speedup is minimal even with more cores.

- Managed: P is higher, but runtime services (GC, JIT) remain serial bottlenecks. Speedup improves but plateaus.

- Native (C++): P approaches 1 for compute-heavy workloads. Speedup scales closer to theoretical maximum, though file I/O and synchronization remain limiting factors.

S(N) = 1 / ((1 – P) + (P / N))

For C++, P can be ~0.95 in compute-bound tasks, yielding near-linear speedup with additional cores. Bash rarely exceeds P = 0.5, while managed languages often hover around P = 0.7–0.8.

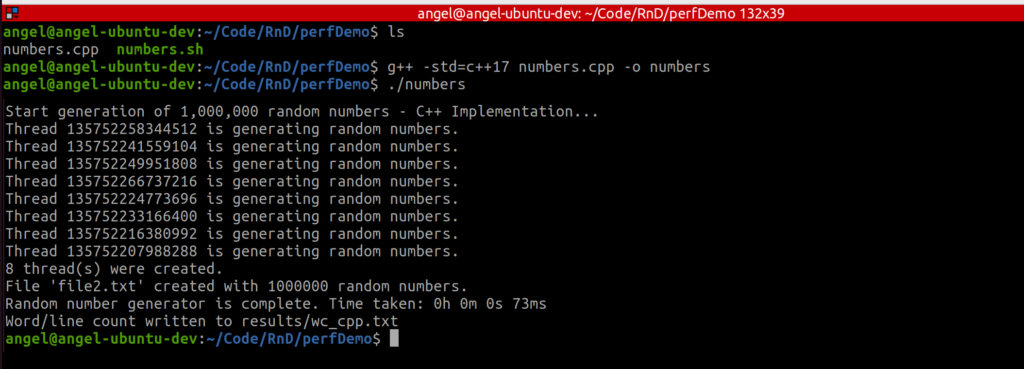

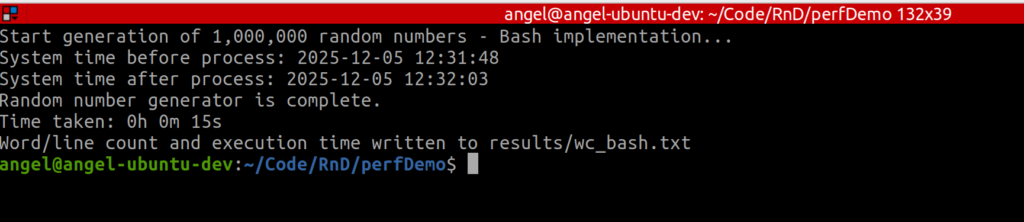

Let’s see this in action

The following code listing and images, written in C++ and Bash demonstrate this

C++ Code

/*

File: numbers.cpp

Written by: Angel Hernandez

Requirement(s): Random generation of 1,000,000 numbers using multiple threads

Compile with: g++ -std=c++17 numbers.cpp -o numbers

*/

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

#include <filesystem>

#include <random>

#include <vector>

#include <chrono>

#include <sstream>

#include <thread>

#include <map>

#include <mutex>

namespace fs = std::filesystem;

#define CLEAR_SCREEN() std::cout << "\033[2J\033[H"

int main() {

const int items_to_create = 1000000; // 1 million numbers

const char* filename = "file2.txt";

const char* resultDirectory = "results";

CLEAR_SCREEN();

std::cout << "Start generation of 1,000,000 random numbers - C++ Implementation...\n";

if (fs::exists(filename))

fs::remove(filename);

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

// Vector to hold random numbers

std::vector<int> numbers(items_to_create);

// Track threads used

std::mutex map_mutex;

std::map<std::thread::id, bool> threads;

// Decide how many threads to use

auto num_threads = std::thread::hardware_concurrency();

if (num_threads == 0) // fallback if hardware_concurrency not available

num_threads = 4;

// Worker function

auto worker = [&](int start, int end) {

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> dist(0, 10000);

static thread_local std::minstd_rand rng(std::random_device{}());

for (auto i = start; i < end; ++i)

numbers[i] = dist(rng);

auto tid = std::this_thread::get_id();

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(map_mutex);

if (threads.find(tid) == threads.end()) {

threads[tid] = true;

std::cout << "Thread " << tid << " is generating random numbers.\n";

}

}

};

// Spawn threads

auto start_idx = 0;

std::vector<std::thread> thread_pool;

auto chunk_size = items_to_create / num_threads;

for (unsigned int t = 0; t < num_threads; ++t) {

auto end_idx = (t == num_threads - 1) ? items_to_create : start_idx + chunk_size;

thread_pool.emplace_back(worker, start_idx, end_idx);

start_idx = end_idx;

}

// Join threads

for (auto& t : thread_pool)

t.join();

std::cout << threads.size() << " thread(s) were created.\n";

// Write results sequentially

{

std::ofstream outfile(filename);

for (auto num : numbers) {

outfile << num << "\n";

}

}

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto elapsed_ms = std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::milliseconds>(end - start).count();

// Break down into hours, minutes, seconds, milliseconds

auto elapsed_seconds = elapsed_ms / 1000;

auto hours = elapsed_seconds / 3600;

auto minutes = (elapsed_seconds % 3600) / 60;

auto seconds = elapsed_seconds % 60;

auto milliseconds = elapsed_ms % 1000;

// Store formatted time in a string

auto time_taken = "Time taken: " +

std::to_string(hours) + "h " +

std::to_string(minutes) + "m " +

std::to_string(seconds) + "s " +

std::to_string(milliseconds) + "ms\n";

std::cout << "File '" << filename << "' created with " << items_to_create << " random numbers.\n";

std::cout << "Random number generator is complete. " << time_taken;

fs::create_directories(resultDirectory);

// Count lines and words

auto lineCount = 0;

auto wordCount = 0;

std::string line;

std::ifstream infile(filename);

while (std::getline(infile, line)) {

++lineCount;

std::istringstream iss(line);

std::string word;

while (iss >> word) {

++wordCount;

}

}

infile.close();

auto now = std::chrono::system_clock::now();

auto now_c = std::chrono::system_clock::to_time_t(now);

std::ofstream wcfile("results/wc_cpp.txt", std::ios::app);

wcfile << "Date: " << std::ctime(&now_c);

wcfile << "Line count: " << lineCount << "\n";

wcfile << "Word count: " << wordCount << "\n";

wcfile << time_taken << "\n";

wcfile.close();

std::cout << "Word/line count written to results/wc_cpp.txt\n";

return 0;

}

Bash Code

# File: numbers.sh

# Written by: Angel Hernandez

# Requirement(s): Random generation of 1,000,000 numbers

clear

echo "Start generation of 1,000,000 random numbers - Bash implementation..."

# Remove old file if it exists

rm -f file1.txt

# Record start time

SECONDS=0

start_time=$(date +"%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S")

echo "System time before process: $start_time"

# Generate 1,000,000 random numbers

for i in {1..1000000}

do

echo $RANDOM >> file1.txt # Append random number to file

done

# Record end time

end_time=$(date +"%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S")

echo "System time after process: $end_time"

# Calculate elapsed time in seconds

elapsed=$SECONDS

# Convert elapsed seconds into hours/minutes/seconds

hours=$((elapsed / 3600))

minutes=$(((elapsed % 3600) / 60))

seconds=$((elapsed % 60))

echo "Random number generator is complete."

time_taken="Time taken: ${hours}h ${minutes}m ${seconds}s"

echo $time_taken

# Create results directory and write stats

mkdir -p results

{

echo "Date: $(date +"%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S")"

echo "Line count: $(wc -l < file1.txt)"

echo "Word count: $(wc -w < file1.txt)"

echo $time_taken

echo -e "\n"

#echo -e "$(time_taken)\n"

} >> results/wc_bash.txt

echo "Word/line count and execution time written to results/wc_bash.txt"

Conclusion

By grounding practical coding decisions in Amdahl’s Law and Big O notation, engineers can better anticipate scalability ceilings and algorithmic bottlenecks. Bash offers agility, managed languages balance productivity and abstraction, while C++ delivers raw efficiency. The art of interop lies in balancing these strengths to design workflows that are both portable and performant.

References

Amdahl, G. M. (1967). Validity of the single processor approach to achieving large-scale computing

capabilities. AFIPS Conference Proceedings, 30, 483–485. https://doi.org/10.1145/1465482.1465560

Cormen, T. H., Leiserson, C. E., Rivest, R. L., & Stein, C. (2009). Introduction to algorithms (3rd ed.).

MIT Press.

Kernighan, B. W., & Pike, R. (1984). The UNIX programming environment. Prentice Hall.

Stroustrup, B. (2013). The C++ programming language (4th ed.). Addison-Wesley.

Gosling, J., Joy, B., Steele, G., & Bracha, G. (2014). The Java language specification (Java SE 8 ed.).

Addison-Wesley.

Richter, J. (2012). CLR via C# (4th ed.). Microsoft Press.